By Apophia Agiresaasi, Global Press Journal Uganda

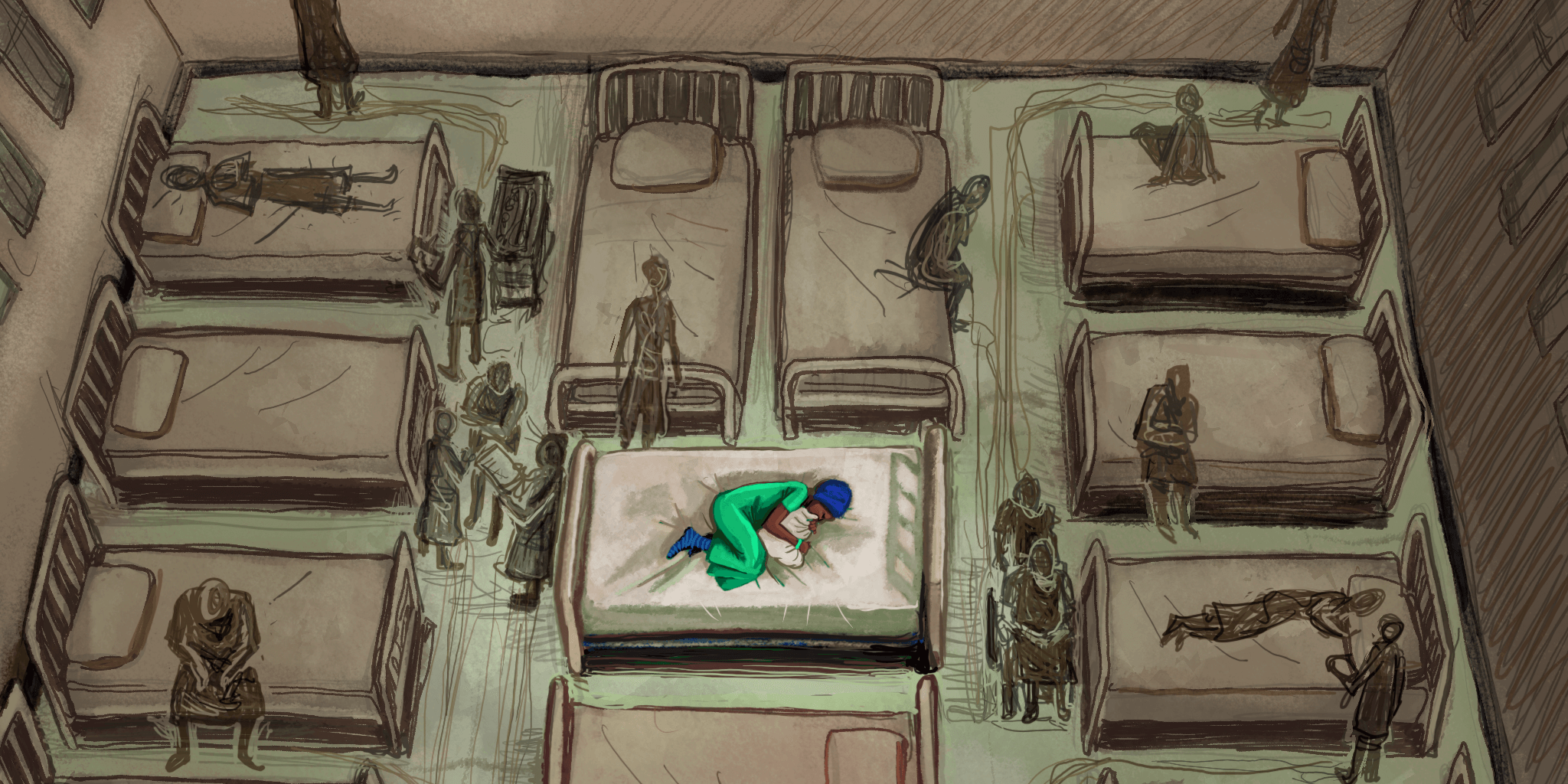

Photo Credit: Illustration by Matt Haney/Global Press Journal

This story was originally published by Global Press Journal.

KAMPALA, UGANDA — The first time CJ was hospitalized for bipolar disorder, she alleges, a staff member who worked in security raped her one evening. She had been admitted at Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital, Uganda’s only national mental health hospital, which is about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) east of Kampala. That night, CJ remembers trying to defend herself, pushing the man so he would get off her, then falling into a trench.

The next day, she reported the incident to hospital administrators. They did not believe her.

“The nurses at the hospital forced me to bathe,” says CJ, who asked to be identified by her initials to protect her identity.

Although the medical personnel at the hospital did a test after she reported the incident, they found she had a urinary tract infection. The evidence was insufficient to prove she had been raped. By bathing her, they had already tampered with any evidence.

During the month and a half CJ was hospitalized, it wasn’t the first time the hospital staff member had tried to rape her. It was the only time he was successful.

CJ says many cases of sexual assault occur at the hospital. Most of them, she says, are perpetrated either by staff or fellow patients. A 2022 study published in BMC Public Health, a health journal, documented the cases perpetrated by fellow patients.

The hospital rarely investigates the reported cases, CJ says. “They are dismissive. They won’t listen,” she says. “They say you are telling lies. You are just having an episode.”

The experience has left an indelible mark on CJ, who believes it has slowed her recovery process. “I stayed longer on medication than I should have,” she says.

About 32% of Uganda’s approximately 43.7 million people have a mental illness, according to 2022 data from Uganda’s health ministry. That’s higher than previous national estimates of 24%, suggesting stigma around mental health — which is pervasive in Uganda — may have masked the real numbers, according to the Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal.

Uganda is also ranked among the top six countries in Africa in rates of depressive disorders, while 2.9% live with anxiety disorders. About 5.1% of women and 3.6% of men are affected.

The country’s primary care system is poorly funded and short-staffed. There are only 53 psychiatrists in the country, according to a 2022 study in the Lancet. That’s roughly one psychiatrist per 1 million residents, which is much lower than the global average of 40 psychiatrists per 1 million people, according to a 2017 study published in Health Services Insights, an international health care journal. Most of Uganda’s 53 psychiatrists work in big cities as university lecturers and researchers, not as clinicians, according to the Lancet.

But lack of mental health services is only part of the problem those struggling with mental illnesses face. According to a 2014 investigation into psychiatric hospitals in Uganda, sexual assault is among the human rights abuses common in the country’s mental health institutions. The study in BMC Public Health also reveals that women with mental illnesses were vulnerable to rape both in communities and in mental health institutions.

Dr. Byamar Brian Mutamba, the deputy executive director of Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital, says that though uncommon, there have been cases of rape at the hospital, some of which are still in court. He says CJ’s alleged assault happened before he joined the institution but declined to comment further on the matter, saying it is still active in court.

“We may have challenges in our service,” Mutamba says, adding that the facility has a policy in place to protect clients. “We are mindful that people living with mental illnesses are vulnerable to abuse, [and] it obliges us to work for a certain standard.”

In January, mental health advocacy groups in Uganda released a statement asking the Ministry of Health and Uganda police to investigate allegations that patients at Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital are being sexually abused while in the hospital’s care.

In the statement, they also decried the harsh living conditions patients seeking mental health care are forced to endure, including congestion in hospitals and forced hospitalization and treatment. The advocacy groups gave the government two months to act before they would take legal action. At the time of the interview, they had yet to file a case and were awaiting communication from Uganda’s Ministry of Health.

The ultimatum by mental health advocacy groups also shed light on some of the loopholes in prosecuting rape cases involving women struggling with mental health issues, a situation that complicates efforts to seek justice. To address this, a Ugandan organization, the Disability Law and Rights Center, is working to equip the judiciary with necessary tools to handle these cases and ensure those affected receive justice.

Agnes Natukunda, a lawyer in Kampala, has handled cases involving people with mental illnesses who have been violated and are unable to get justice. The main challenge, she says, is adducing evidence in court.

“Many can’t speak in court. [The] court would want her to speak. You go to court, she can’t answer. Justice can’t be delivered unless she is pregnant and has delivered and a DNA test is carried out to bring evidence that can be corroborated,” she says.

In one such case, Natukunda says her client sometimes withdrew from testifying because she wasn’t mentally stable enough. What helped the case was that there were witnesses. Her client’s relatives had seen the alleged perpetrator seeking her out, so they gave evidence in court. Still, the case was eventually dismissed for lack of evidence.

Derrick Kiiza, executive director of Mental Health Uganda, a local nonprofit, also confirms these cases are common. However, they are not documented, as those affected rarely report them.

He adds that in some psychiatric centers, clients have to be admitted with caretakers to protect them.

Shamim Nalule Rukiyah, a lawyer with Musangala Advocates and Solicitors, a law firm in Kampala, has worked on several cases in which women who struggle with mental illnesses were sexually abused. Nobody believes what they say, she says. One such case ended in acquittal because the person affected could not give evidence in court.

“Nobody believes them, and that gets them more mentally disturbed. The perpetrators know there is nowhere they will go and get justice,” Shamim says.

The penal code, which has an insensitive description of people with mental illnesses, worsens the problem, Shamim adds. It defines people with mental health issues as “idiots,” which says a lot about the insensitivity with which their cases are handled.

“Why use that word?” Shamim says. “Would you go and report or go through trial when you know everyone is looking at you as an idiot?”

Already, rape cases in Uganda rarely result in convictions. Of the 1,623 cases of rape reported to police in 2022, only 557 were prosecuted, and only three secured a conviction.

In addition, many rarely report these crimes while some report late. The 2020 National Survey on Violence in Uganda identified several barriers contributing to this phenomenon. One major hurdle is the fear of retaliation, especially when the abuser is a spouse or relative. There is also a lack of trust in the legal system and little accountability for perpetrators. People who experience sexual abuse also face the burden of stigma and social isolation.

The lack of sensitivity in the way authorities handle such cases ensures that few are reported, further perpetuating the violence as perpetrators get away with their crimes, says Patricia Atim P’Odong, the project officer of Disability and Law at Makerere University’s Rights Centre School of Law, an organization that champions disability rights.

Atim says the institution has been training the judiciary since February on how to handle cases of people with disabilities, including those struggling with mental illnesses. So far, they have noted an increase in cases of women with mental health who have been sexually assaulted. Some of the cases have taken place within mental health institutions and others outside, Atim says.

Women with disabilities are more affected and more often excluded by the justice system, Atim says, given the patriarchal nature of Ugandan society. Already, they have less access to legal services, suffer more violence than men, are less educated, have less income and have fewer employment rights than men.

In addition to training the judiciary, Atim says, Disability and Law has developed draft rules — which have yet to be made public — for how the judiciary should handle cases of people with disabilities. The group has submitted them to the judiciary and is awaiting approval from the court.

“These will enable judicial officers who did not receive the training to be able to use them and those who attended training can always refer to them. If court adopts the rules, many more judicial officers will access them,” Atim says.

But it is a challenging situation for prosecutors to navigate. Jacqueline Okui, public relations officer at the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, says sometimes clients who can’t speak in court are the only witnesses. Other times, the caretakers or parents involved get compromised and withdraw the case.

Elizabeth Brenda Achola, program officer for the Women’s Probono Initiative — Uganda, a local nongovernmental organization that promotes justice for women, says the group is handling two such cases of women violated in mental health institutions. The government should take it as a matter of urgency, Achola says, as women who are sexually violated tend to have mental relapses and are more in need of psychosocial support.

Hasfa Lukwata, the commissioner for mental health and control of substance abuse in the Ministry of Health, says the ministry has written to Butabika National Referral Mental Hospital, asking officials to respond to allegations, and is waiting for a response. She did not respond to additional requests for comment on the state of mental health facilities in Uganda.

Philip says his foster daughter, 31, was also raped while receiving care at a referral hospital. At one point she was at the hospital, then later found herself in a man’s home. She got pregnant and now has a 6-year-old son.

Since then, Philip, who asked to be identified only by his first name to protect his foster daughter’s identity, says she has lost trust in health facilities and is hesitant about seeking health care services. She has also become more suspicious of people. When she gave birth, an orphanage took the baby, which Philip believes further traumatized her. Although she has given birth before — pregnancies Philip says he believes also resulted from rape — she is extremely protective of the babies.

This story was originally published in Global Press Journal.

Global Press Journal is an award-winning international non-profit news publication that employs local women reporters in more than 40 independent news bureaus across Africa, Asia and Latin America.